The 1922 Nosferatu is one of the great works of silent cinema and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau was one of the great directors in all cinema. As is well-known, Nosferatu is the first filmed version of Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula. The film makers were unable to obtain rights to the book so they thinly disguised the source by changing the names of the characters and locations. Interestingly, with all that, it is more faithful to the novel than many later efforts.

The story's outline, also well-known--to the point of being iconic--is as follows. English real-estate agent Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania so he can offer a certain Count Dracula properties in England; the Count ostensibly wishes to relocate there. Dracula, who turns out to be a 400-year-old vampire, imprisons Harker in his castle and proceeds to England where he preys on Harker's fiancée Mina and her friend Lucy. Dracula is finally destroyed through the wisdom of Professor Abraham van Helsing in conjunction with the youthful energy of the women's fiancés and friends.

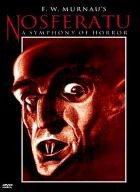

In Nosferatu, as I said, director and writer made several changes, probably for reasons in addition to the copyright dilemma. Dracula becomes Orlok, played by Max Schreck, a stage actor whose real surname means "terror"; England becomes Bremen, Germany; Jonathan Harker becomes Thomas Hutter; his fiancée Mina becomes his wife Ellen; Lucy becomes Ruth; van Helsing becomes Bulwer; and the insect-eating madman Renfield becomes Knock, who, besides being Dracula's familiar, is also Hutter's employer, initially sending him to Orlok's castle. In addition, Orlok is not only a vampire, but a plague spreader, bringing with him thousands of infected rats. As one writer pointed out, there is perhaps a taste of pre-Nazi anti-Semitism in some of the alterations: for one thing, Orlok has the caricatured look of "the Jew" as depicted in German anti-Semitic literature of the period: quite unlike Stoker's tall old man with flowing gray hair and mustache, Orlok is bald, rat-faced, and repellent, with an out-sized hook nose. As an aside, even the name "Orlok" is somewhat reminiscent of "Shylock," Shakespeare's Jewish villain in The Merchant of Venice--the most famous theatrical anti-Semitic stereotype. Vicious rumors of Jews as plague spreaders had been used to justify their continuous wholesale persecution and murder since the middle ages, the irrational hatred that finally culminated in Hitler's Final Solution. Orlok preys on Hutter's young wife, who sacrifices herself to keep him until dawn, thereby causing his destruction; with that image, one can see the "Jew" as the spoiler of racial purity, the evil foreign (read: "Jewish") seducer of the virtuous Aryan woman. In fact, Ellen's martyrdom makes the van Helsing figure (Bulwer) altogether superfluous in this version of the story. It's not a pretty picture, but one that reflects the dangerous, simmering, post WW-I anti-Semitic mindset in Germany that enabled the Nazi takeover and subsequent atrocities. It is unclear whether Murnau was conscious of the implications in the images he was creating.

In any case, Nosferatu is one of the most important works of silent cinema. It is often erroneously referred to as German "expressionism"; nothing could be farther from the truth. While the 1920 Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is expressionistic, with distorted geometry, sets, and a modernist approach, Murnau went out of his way to create as realistic a look for Nosferatu as possible. It is one of the earliest examples of location shooting, and every shot can easily be traced to specific spots in Europe. Interestingly, the 2000 film Shadow of the Vampire, which takes a fictional look at the making of Nosferatu, point outs accurately how very realistic a visualization Murnau was after.

The film has had a hard life. As the studio Prana never got the rights to the novel, Dracula author Bram Stoker's widow obtained a court order to have all negatives and prints destroyed in the 1920s when the bankrupt Prana could pay her no royalties. She never saw the film, by the way. Luckily, prints did survive, though in various states of quality and length.

On DVD, there are two good choices: the Image or Kino versions. Other DVD versions are from poor, usually heavily cut, sources, and must be avoided altogether. It's not an easy choice. The Image version was made from a good 35mm tinted print in the 1990s and runs 81 minutes, the most complete source to that date. There are two musical scores provided on that DVD: a forgettable one by the "Silent Orchestra," and a brilliant organ score by Timothy Howard--surely the best score that has ever been composed for this film. The Kino version is visually stunning, the only DVD made from a recently discovered 35mm tinted negative, the survival of which is an unanticipated, wonderful surprise. Moreover, it runs 93 minutes, partly owing to a slightly slower and more natural projection speed, but also because more scenes survive in this version. It also preserves the original division into five acts. All in all, the Kino edition seems to represent the genuine film created by Murnau. Unfortunately, the release is marred by two unfortunate musical scores: an electronic one that is often more noise than music, and a foolish one that adds comic touches at inappropriate moments. It's a shame Timothy Howard's organ score on Image can only accompany the incomplete 81-minute version. The only solutions are to watch the Kino edition without music, the less complete Image version with the great organ score, or own both DVD editions, each for a different reason.

Review by Robert E. Seletsky

| Released by Image and Kino DVD |

| Region 1 NTSC |

| Not Rated |

| Extras : see main review |