(A.k.a. NINGEN JOHATSU)

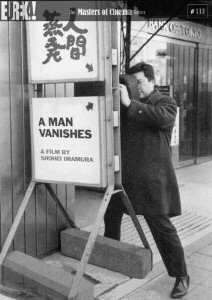

Prolific Japanese filmmaker Shohei Imamura’s celebrated 1967 crime ‘documentary’ A MAN VANISHES opens with an address from Detective Fukuodori Yuzo of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police force. He opens a file at his desk and introduces us to the case of Oshima Tadashi, a 32-year-old plastics salesman who went missing two years previously.

We learn that he went to Fukushima on business in April of 1965 ... and has not been seen since.

An interview with Tadashi’s boss, Mr Oka, gives little clue as to where the man may be but does give an early clue as to the type of shenanigans he may be wrapped up in: he was caught four years earlier embezzling from his employer. Oka’s wife also displays disappointment in Tadashi, especially seeing as though they had taken him in to their home and given him a roof over his head for quite a spell previously.

Also disgruntled with the reputedly quiet bloke is his former father-in-law, and his wife. Even his own sister doesn’t seem overly keen on Tadashi ...

We learn that Tadashi also had four brothers and his father, a farmer by the name of Saicharo, tried his best to be generous to each of them, bestowing them each with acres of land to build their own lives upon.

So, the question surfaces, why did Tadashi deviate from this charmed life so, and how did it contribute to his eventual vanishing act?

Imamura himself conducts the interviews, with his back largely to the camera, squaring up close to his subjects in a confrontational manner, making each exchange seem like a mini-interrogation. Some characters are clearly uncomfortable with exposing their own pieces of the jigsaw – tales of mistresses, backstreet abortions, etc – that they prefer to have their identities hidden behind black bars.

For an expose on the growing trend of missing persons in contemporary Japanese society (91,000 missing people reported in 1967 alone, we’re told), this is unusually stylised fare: much of the starkly contrasting monochrome imagery is extremely noirish, as are the flourishes of carefully placed score. The interview techniques are, as mentioned above, hard-boiled, and the revelations about Tadashi keep on coming – he was a petty criminal, a philanderer par excellence, and so on.

Long and involved, with lots of characters introduced along the way, A MAN VANISHES is nevertheless fluent enough to be consistently absorbing as realist drama – right up until its somewhat expected (by today’s measures) rug-pulling ‘twist’ towards the end.

But even if you’ve sussed that already – or, more likely, read about it in previous reviews – this remains a remarkably focused, tightly edited and well-played ensemble piece. The documentary style doesn’t harm the dramatics none, reserved as they are, and Imamura builds the investigative angle cannily towards a breathless, tongue-in-cheek final act that should have viewers grinning in awe of its sheer audacity.

Eureka’s DVD comes as one of their consistently impressive Masters of Cinema canon, very much the British equivalent of the esteemed Criterion Collection.

The film is presented in its 129-minute entirety, the transfer having been struck from a 35mm negative and offered in the original 1.37:1 window-boxed ratio. The black-and-white images are well contrasted, shade and depth both being striking in their solid renderings. The print used is largely free from debris while fine natural grain suggests this is as authentic a transfer of the film as we’re likely to find. Thank Goodness it’s also in such good shape, despite occasional softness and scratches.

The Japanese 2.0 mono audio also fares quite well, being a mostly clean and consistent track. A disclaimer at the start of playback points out that some of the audio could not be synchronised to images in post-production, and emphasises that this is a flaw of the original recording – and not Eureka’s mastering. Fair enough.

Optional English subtitles are well-written and, despite being white against a colourless background, are easy to read. The thin black border on the text helps.

The DVD opens with a window-boxed monochrome main menu page, which leads into a similarly static scene-selection page where you can access the film via 13 chapters.

Of the bonus features provided, perhaps the most substantial is an 18-minute reflection on the film from writer Tony Rayns. He refers to an interview he conducted with Imamura back in 1984, as well as pointing out nuances and necessary styles employed in the making of the film (such as the need to compensate for filming without sound), and offers interesting titbits of trivia including the fact that Imamura originally intended to follow no less than 26 missing persons cases in the film – but found proved to be far too difficult to pull off. Pertinently, Rayns makes the distinction of the film indulging in "journalistic investigation" as opposed to investigative journalism. It’s a marvellous way of summarising A MAN VANISHES.

This is a highly involving, illuminating featurette – in black-and-white, 16x9 enhanced – that almost compensates for there being no Rayns commentary on this occasion (those who have heard his tracks on the likes of VENGEANCE IS MINE [MoC] and IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES [Criterion] will realise what we’re potentially missing here). Hot off the press, this chat with Rayns was recorded on August 22nd 2011 and remains exclusive to this release.

Next up comes a 9-minute archive interview with Imamura himself. It’s a great informal piece, the erudite but pensive director speaking softly to his son, Daisuke Tengan, round a dinner table as they both chain-smoke. Imamura contradicts Rayns’ recollection slightly (he says the original working title was 24 MISSING PERSONS ... not 26), but gives a little more insight into the subject of his completed film.

There is a certain degree of coolness between these two that is unnaturally fascinating; how the hell did they ever convey emotions to each other at family bashes, for example?!

A 69-second Japanese theatrical trailer for A MAN VANISHES is a welcome addition to the disc, although it’s perhaps most notable for the Nikkatsu logo at the opening. The rest of it is made up of stills from the film accompanied by tabloid-like slogans.

Also included in this impressive set is a 36-page booklet which pleases by virtue of some keen black-and-white photographs and excellent writing. It begins with reflections on the film from Imamura himself, lifted from his 2004 autobiography. Editor Urayama Kiriro offers his thoughts too, as does fan and fellow filmmaker Nagisa Oshima (IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES) in an archive piece from 1967. Excellent stuff.

Masters of Cinema continue to wow with yet another solid release of a film much revered in scholar’s circles but rarely shown commercially. Thanks to this wonderful series, we can now all share in the admiration of one of the great Imamura’s mostly highly praised films.

Bravo to Eureka. Yet again.

Review by Stuart Willis

| Released by Eureka Entertainment |

| Region 2 - PAL |

| Rated 18 |

| Extras : |

| see main review |