Told with precision and an ambiguity that makes its surface scares twice as effective, Booth is similar to a great labyrinthine puzzle, evoking disturbing questions of guilt and culpability alongside genuinely disturbing phantoms. Posing unsettling questions of existence for each enigmatic half-answer it offers, the film refuses to lay bare its secrets upon the emotionless table of criticism, offering further enigmas with repeated viewings. Director Yoshihno Nakamura toys with expectation. His plot-twists really shock, the roots of his supernatural nightmares planted in the stony soil of the everyday.

Coating viewers with a sickly gleam of dread, this story of cyclical fate, internal hatred, and emotional justice features Shogo (Ryuta Sato), an arrogant and self-absorbed star of "Tokyo Love Lines," a popular call-in radio show. Dispensing advice to the lovelorn when, in fact, he has no true concept of emotional attachment, Shogo's soul is marred by betrayal, possible murder, and daily cruelty. He begins to realize the depth of his sins -- and the dire straits he's placed his soul in -- when a vengeful spiritual force (first introduced in the beginning as a jilted lover who committed suicide) attacks his identity, memories, and sense of self (before visiting him personally), Shogo finds himself dissected by friend and foe alike. Forced to broadcast his show from 'Studio 6,' -- a decrepit, moody, depressing area as filled with physical grime as it is with spiritual malevolence -- Shogo discovers that the last time a DJ broadcast there he hung himself.

A character in its own right, studio 6 breaths with increasing menace and intimacy, stronger in its immediate presence than even the spiritual force tearing away Shogo's emotional wall. Despite an exterior show of bravado, Shogo soon doubts his sanity as disembodied voices scream "You're a liar!" In an especially dark touch, voices that may or may not belong to the living list his multitude of crimes in a method as stylistically inventive as it is thematically jarring, recounting his personal sins as their own experiences so only he realizes their true depth. The stylistic method in which the director merges ghost-like flashbacks with present-day shots from the radio booth, alerting us to the fact that each caller's tragic history is, in fact, Shogo's own, suggests the horrific (if well deserved) flood of the supernatural into the context of everyday reality. Its fascinating and horrible to watch this character's once-firm belief in the logical parameters of existence deteriorate. Assailed on all sides, betrayed by both his friends and his buried sense of guilt, this story owes just as much to the surrealistic dream-logic and emotional unease of Kafka as to the primal simplicity of ghost lore. Spirits of the dead could just as well be Shogo's conscience.

Booth suggests that there are no clean-cut answers to a world more charnel house than confessional, juxtaposing the natural and spectral in such a way as to reflect the insecurities and wonders of each. Meanwhile, and with undeniable understanding of the human psyche, Nakamura invites panic and pathos, finding the source of the uncanny in the sordid depths of his character's guilt. Invoking the hallucinatory fever of a nightmare with dense camera compositions, coaxing meaningful performances from a believable cast, Yoshisno's direction lends innovation to what in less capable hands would have been nothing more than another ghost story. Far from another Asian remake, Booth is every bit as much a character study as horror show. There is so much more to fear in this tragedy of atonement than the appearance of the spectral. Existence itself is haunted, not only by the dead but by the living who Shogo has done wrong. Hell, his own subconscious hates him! In this shadow-show of self-deception and grief, the dread mechanisms of internal conflict mirror (and lend further substance to) a finely layered puzzle of culpability.

A scathing story of a mind in conflict against itself and spectral wrath, Shogo's unsympathetic (if, at times, understandable) character is fascinating as a portrait of mental and emotional deterioration. His ego is the true victim, and the dark heart of the film revolves around loss of Self, identity, and emotional stability. Perhaps the most dreadful threat is the rapidity with which our frail perceptions and understanding of both ourselves and the universe may be peeled away by even the smallest disruption of natural order. Beneath the finite door of sensory logic and surface appearances is undiluted terror. This door is opened with poetic grace and a vivid understanding of the human mind by cast and crew. As Shogo's mind falters, the director suggests with carefully orchestrated compositions a surreal crack in the dividing line between the world of the living and the world of the dead, between reality and nightmare. He creates, in fact, a borderland -- a sense of separation -- that is itself echoed by the realistic strife in Shogo's everyday world. Booth is the depiction of a yawning black void forcing its foul presence between appearances and internal truths far more significant . . . . and decidedly more threatening.

Creating a world/context where neither the characters (or we) ultimately know what is real or illusion, history or lie, both Shogo's reality/sense of self and personal history is attacked; so too is the belief in objective reality, subverted by a perspective rooted somewhere in the shadows of both. Immediately we're asked who -- if anyone -- we can ally ourselves with; who do we believe? And do the characters themselves know where their own lies begin or end? The director takes away the traditional safety nets afforded us by traditional cinema wherein we're encouraged to affix our beliefs to a main character. Here, in both story and format, our 'hero' is untrustworthy at best. At worst, Shogo's psyche is a train wreck. In a brave stylistic move, Nakamura mirrors the subtext of untrustworthy perspective -- and the threat of a world without sense -- by mirroring the fragmented structure of the narrative with deeply subjective POV shots that, while allowing us to see as through Shogo's eyes and feel from his heart, contradictorily provoke us to further question his part in a plot that unfolds with the finality of an unwinding funeral sheet.

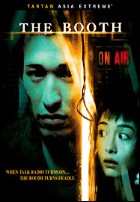

Receiving Tartan's customary respect and dedication to quality, Booth receives a presentation in anamorphic widescreen, preserving the gloom-laden atmosphere of disturbing interior shots. Characters are clearly defined with luscious skin tones shaded by the director's low-resolve lighting choices, allowing us to better refresh ourselves in cinematography that blends rough urban sprawl with the sinister resonance of a dream. Audio does its job in Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround Sound and DTS Surround Sound 5.1. Extras for this deconstruction of identity are satisfying if not unique, including "The Making of The Booth," a mini-featurette discussing the preparation of the story, and the filming challenges of the feature, followed with a "Q & A Session" wherein some of the same material is covered, an interview with the filmmakers, and the original trailer.

Evoking atmosphere as a symbolic reflection of internal conflict, Booth employs fine actors in a dialogue-rich script to create a ghost story devoted to character. Like a cold kiss in the dark, the unexpected quickly blossoms into terror. Following Shogo's internal journey from confidence and skepticism to slowly mounting dread and, finally, panic, Toshihiro Nakamura captures the essence of quite internal dread. Unsure who (or what) we should quite believe, the uneasy nature of the poignant subtext lingers long after the picture fades to black. Proving that what we don't see is often more frightening than what is shown, Booth is an undeniably chilling nightmare of consciousness whose principle nightmare is evoked in character's (and our own) sense of revelation. A frightening and philosophical shock show!

Review by William P Simmons

| Released by Tartan Asia Extreme USA |

| Region 1 NTSC |

| Not Rated |

| Extras : see main review |