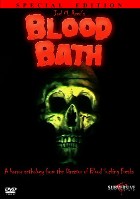

An admitted refutation of good taste, Joel M. Reed's Blood Bath attempts to do much with little. Trying to compensate for a senile, cliché-riddled storyline with cheap surface scares (and still cheaper effects), director Reed somehow manages to make this exploitation vehicle enjoyable - operating on the fuel of shlock-shock rather than storytelling sincerity.

While in no way a good film, Blood Bath is enjoyable despite itself. Reed never pretends to be anything but a celluloid carnival barker, parading his stubby-horned ghouls, wise-jiving pimped-up ghosts, and funeral freaks with pride if not taste. He inspires a crude sense of the monstrous in otherwise routine tales, enthusiasm lending inept coincidences (and more than a few plot inconsistencies!) good-natured humor.

While the general goofiness of the surface action fails to inspire scares, Reed's warped treatment of lewd lunacy brings his catalogue of beasts and breasts the status of a cult curiosity, appealing to freak-show mentality while abandoning any real pretense of maturity. Oddly enough, there is barely any blood, despite the promise of the title.

A man whose personal life is as interesting as his films, Reed slings nonsense against the camera with the gusto of a surrealistic painter attempting to find a face for our culture's madness. Either that, or he just knows how to party! Either way, a good ludicrous time is to be had in this sleazy slab of deadpan. Creator of such legendary peons to bad taste as Bloodsucking Freaks and Night Of The Zombies, Reed is not afraid to fondle themes that saner filmmakers would flee from. Not only does he not shy away from stylistic and plot excess, he embraces them!

Short forms have always been most successful in evoking emotions of dread and titillation, as our ancestors well knew, spinning horrific tales long into the night. Later, with the coming of written language, storytellers translated their cultural fears into literature. Most popular were frame collections, wherein individual stories were unified and lent structural unity by a central story that tied the disparate elements together. Infamous EC Comics did much the same thing, employing as their frame device not so much a story but characters that supplied a continuing format for creepy yarns. It was a small jump from page to screen; the earliest film to employ the frame-format was the classic Dead Of Night. Years later, during the heyday of Hammer Studios, Amicus, their most successful competitor, also began to specialize in the form, churning our Asylum, The House That Dripped Blood, and others. Of course the frame anthology has modern incarnations as well, from the big-budget spectacles of Creepshow to such Z-budget black sheep as Night Train To Terror. None of these hawk worse production values and more unintentional humor as Reed's Blood Bath.

Reed's collection of carnality and crudeness succeeds as a dark comedy of grotesqueries but fails as n intelligent (or horrific) film. Despite its thrift-store theatrics, lack of believability, and awkward performances, Blood Bath rests firmly in the 'so-good they're bad' category of Camp. Reed's very moxy has to be admired (if not his storytelling ability). Some scenes repulse and scare on the level of a pre-planned boo!, and some are so crazy in execution that you cant help but admire the filmmaker's audacity.

Containing four tales, Reed burrows a note from Amicus, situating his fictions in a convenient yet suitably spooky environment as filmmakers tell macabre tales around the dinner table - a modern incarnation of the campfire -- with each personality fitted to tell his/her special ghostly story. One story features a hitman who finds ironic justice (again similar to Amicus sensibilities, particularly those tales scripted by Robert Bloch, whose fiction specialized in cruel humor). We also have a mystical coin that transports its owner back in time (God help me - the effects here are just plain nutty!), a ghost which haunts a wealthy old man's money vault, and a martial artist whose ambition to attain dominance reveals a horrible secret - this last story features one of the worst special effects to ever grace the screen!). Devilish daughters, amputations, and rampaging demons makes this cinematic equivalent to a drunken Halloween Party.

Blood Bath shares with the director's near pornographic masterpiece Bloodsucking Freaks a drab, murky film stock whose lighting and grimy interiors add to the moral bankruptcy of the characters and situations - properly reflecting the mood and tone of the stories. Yet despite such surface similarities, Blood Bath is quite different in attitude than its better known companion, exchanging the morose misanthropy of Freaks for cheese. No bad thing if you're in the mood. Simply put, this is a harmless diversion through the back-flap of the freak tent, something I'm sure Reed would be proud of.

Subversive does a fine job with Blood Bath, presenting it in anamorphic widescreen in its original aspect ratio (1.85:1). Colors are bold and sharp, and the picture is generally well defined. Some grain and softness is apparent, but considering the source print, these are small complaints. Audio is offered in both original mono and Dolby 2.0 Stereo.

After determining the basic worth of a film, extras are where we look to gauge the value of a disc. Happily, Subversive Cinema is up to its old tricks, providing devotees of creepy camp with enough supplements to keep us busy for hours! These include a feature-length commentary with the director, a bizarre good time as Reed's attitude and wit broadens our enjoyment of his approach to filmmaking. Coming across as affable and self-effacing, his humor and wise-cracking mentality are infectious. This is one of the rare cases where I enjoyed the extras better than the film itself. Subversive has done a fine job creating a document of exploitation history in the substantial featurette "Taking A Blood Bath: Making 70s Indies in New York." This retrospective detour through the wheeling and dealing exploitation game is educational and funny. Interviews with cast and crew are interwoven together so as to speed up the pace while supplying a variety of opinions on such subjects as nudity in the movies, funding, and the various shady dealings that funded exploitation films. Featuring Jerry Lacy (Don Savage), Sonny Landham (Bodyguard), Ron Sullivan (aka Henri Pachard), and Reed, this is a crash-course of gorilla filmmaking. Subversive trailers, talent bios, and groovy replicas of lobby cards (and a theatrical poster) round out this tribute to Midnight Movies, lending it a nostalgic Grindhouse sentiment.

Review by William P. Simmons

| Released by Subversive Cinema |

| Region 1 - NTSC |

| Not Rated |

| Extras : |

| see main review |